San Antonio Trying to Figure Out the Best Way to Preserve the Edwards Aquifer

The Frio River snaked south through the hills of Uvalde County, its clear waters coursing over a bed of white, fractured limestone in the recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer.

The Frio River snaked south through the hills of Uvalde County, its clear waters coursing over a bed of white, fractured limestone in the recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer.

The river had flowed into — and underneath — Dripstone Ranch, nearly 2,000 acres of undeveloped ranchland named after a system of nine caves that open into the hillsides and stretch hundreds of feet beneath the earth. One of them, Queen Frio Cave, contains an underground stream that flows swiftly east for San Antonio residents to drink.

To those in the business of acquiring land to protect San Antonio’s water supply, Dripstone had developed a reputation over the years as an alluring and elusive prospect, earning it a nickname.

The White Whale.

“Dripstone. That’s a big one,” said Francine Romero, who chairs an advisory board that oversees the city’s Edwards Aquifer Protection Program. “They used to call it the White Whale, the guys from the Nature Conservancy, because it was just so attractive to the program.”

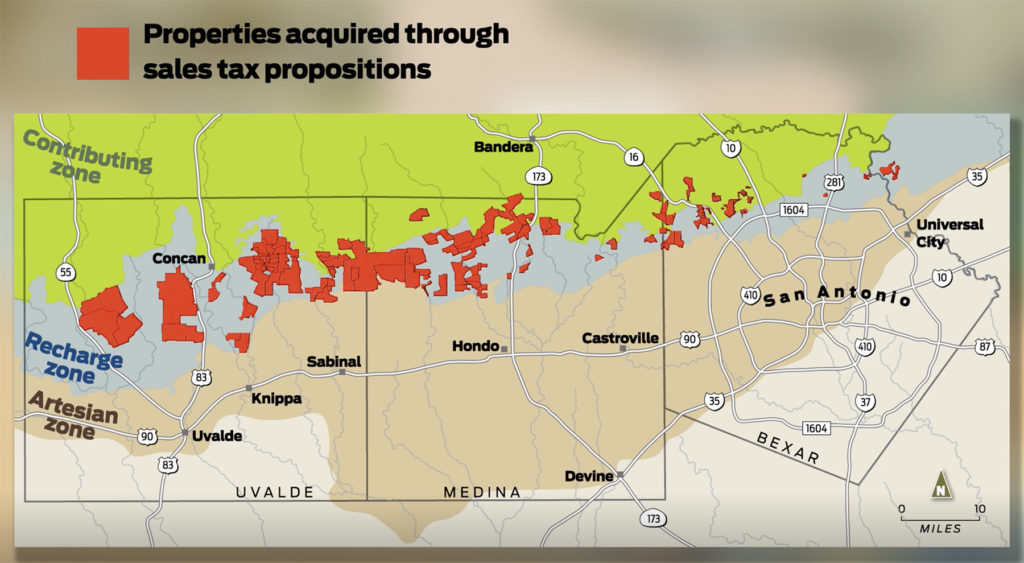

Voters authorized the EAPP two decades ago to prevent contamination of the water that recharges the aquifer — a source of drinking water for more than 2 million people — and to maintain enough permeable surface to allow it to refill. Save for a relative handful of outright land acquisitions, the program has accomplished this mostly through the purchase of conservation easements, a less costly transaction under which a landowner keeps the deed to the property but agrees to limit development. Read full article

See the video of the Edwards Aquifer Recharge zone area in Texas

Coronavirus is a Common Virus in Livestock Herds and Poultry Flocks Seen Routinely Worldwide

By Kay Ledbetter via Texas A&M Agrilife

Many people are hearing about coronavirus for the first time as the China strain, COVID-19, affecting humans causes concern all across the world. But coronaviruses are not new to livestock and poultry producers, according to a Texas A&M AgriLife veterinary epidemiologist.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, common human coronaviruses usually cause mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses, like the common cold. Most people get infected with one or more of these viruses at some point in their lives.

But the CDC is now responding to an outbreak of respiratory disease caused by a novel or new coronavirus that was first detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China.

“Coronavirus is a common virus in livestock herds and poultry flocks seen routinely worldwide,” said Heather Simmons, DVM, Institute for Infectious Animal Diseases, IIAD, associate director as well as Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service’s associate department head and extension program leader for Veterinary Medical Extension. IIAD is a member of the Texas A&M University System and Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

More Rains Needed for Texas Ranchers to Avoid a Drought.

Brief Synopsis of the USA Today original article, by Rick Jervis

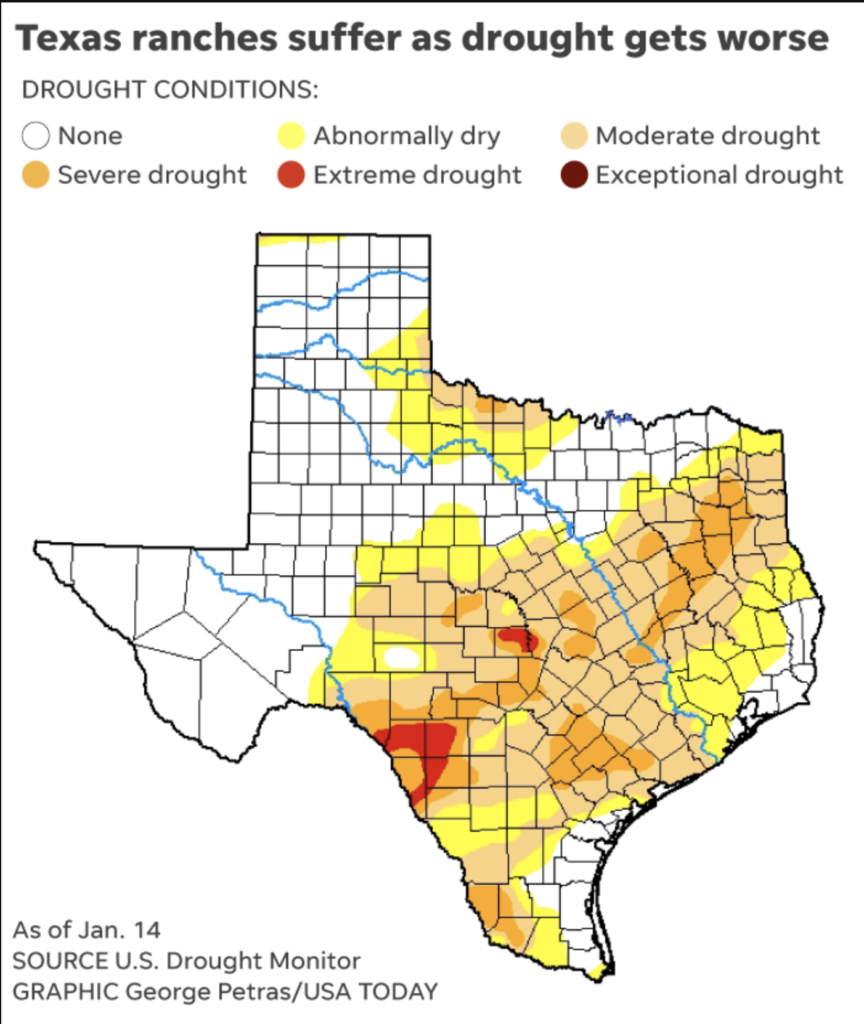

Texas cattle ranchers face tough decisions to cull or sell herds as the drought deepens in some regions of Texas. The rains occurring January 21st and 22nd were a welcome relief for some Texas ranchers. Ranchers are hopeful that the lack of recent rains this winter and the dry start of 2020 are not foreshadowing a drought, like the devastatingly dry year experienced in 2011.

Texas cattle ranchers face tough decisions to cull or sell herds as the drought deepens in some regions of Texas. The rains occurring January 21st and 22nd were a welcome relief for some Texas ranchers. Ranchers are hopeful that the lack of recent rains this winter and the dry start of 2020 are not foreshadowing a drought, like the devastatingly dry year experienced in 2011.

Texas is the leading cattle producer in the US, capturing 15% of the market. When droughts persist, non-irrigated pastures that cattle are dependent on don’t produce enough grass to maintain the herds.

Ranchers are often forced to sell off their herds when the rains don’t materialize. The drought in 2011 saw most of Texas average only 15 inches of rain for the year. Ranchers were forced to sell off their herds and coupled with wildfires, the costs were estimated at $8 billion.

Statistics released this week by the U.S. Drought Monitor showed more than half the state as abnormally dry – with 37% of the state in moderate drought conditions and about 11% of the state in severe drought. So to Mother Nature, we say, let it rain!

Largest Ranch Sales of 2019 Per Land.com

Highlights of an article by Lands of America on Land.com

Lands of America has listed the following properties as the most expensive ranches sold in the US in 2019.

- $70,000,000 – Las Veras Ranch, 1,800 acres with 2 miles fronting the coastline in Santa Barbara, CA, nestled between the Pacific Ocean and Los Padres National Forest. Donated to UC Santa Barbara, by Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway.

- $54,038,785 – La Bandera Ranch, the southwest Texas ranch in Dimmit County near Carrizo Springs is a high-fenced hunting spread featuring 18,000 acres and a full-service hunting operation to provide world class deer, quail and dove hunting.

- $43,250,000 – 60.2 acres, Disney Land, Florida was sold that is a development site uniquely positioned between Disney World, Universal, Sea World, Premium Outlets and the Orange County Convention Center along the Interstate 4 (I-4) corridor.

- $43,940,500 was asking price – Sulphur Bluff Ranch features 13,400 acres and was reportedly sold in conjunction with the neighboring Hageman Reserve. The combined asking price was $84,000,000.

- $39,950,000 was asking price – Sold with Sulphur Bluff Ranch, the 1,000 acre Hageman Reserve’s crown jewel is the 65,000-square foot European influenced multipurpose lodge.

- $39,555,000 was asking price – The Leon County K B Carter Ranch spread includes 14,650 acres with a major cattle ranching operation, 2,000 crop producing acres and 14 miles of Trinity River frontage.

- $39,500,000 was asking price – The 32,000 acre Circle Ranch in the Diablo Mountains of far-West Texas has had only three owners since Obadiah Bounds pioneered the ranch in 1879.

- $34,027,500 was asking price – Lion Mountain Ranch is just 20 minutes from downtown Fort Davis and features 17,450 acres of big Mule Deer country, with some of the most scenic canyon lands in the Davis Mountains of Far West Texas.

- $29,750,000 was asking price – The 7,325 acre Blue Creek Ranch offers a hunters paradise with a combination of deer, trophy bass fishing, and bird and waterfowl hunting that is hard to compare. Located in southern Wharton County, it’s just over an hour from Houston.

- $29,547,200 was asking price – The West Powderhorn Ranch encompasses 10,016 acres along the Texas Gulf Coast near Port ‘O Conner and Matagorda Bay. Mainly high-fenced, it is used primarily as a cattle ranch and hunting ranch, with bobwhite quail, native whitetail deer, and turkey hunting. Other large game animals include Impala, Eland, Addax, Sambar Deer, and Axis Deer.

How to Buy a Ranch

Article by Sarah Max, Worth Magazine

In 2002, Washington State investment manager Thomas Hanly, a native of Montana, decided he was ready to fulfill his childhood dream of owning a ranch. He wanted rolling grasslands, live water and mountain views, and searched the big-sky state until in 2002, 2003 and 2004, he bought three adjacent ranches totaling 1,300 acres and bordering national forest on two sides.

Then the real work began. With the help of his wife and his brother, Hanly set about restoring streams, fixing fences and building two houses, one for his family and one for a ranch manager. It was a major undertaking, especially with a demanding job two states away, but Hanly says the investment has already yielded profound returns. “My kids spend every summer in Montana,” says the father of four. “They’ve competed in the rodeo and learned to fly-fish.”

Class-A ranches—those in the best locations, with profitable cattle operations and wildlife habitat—weathered the financial crisis and recovered quickly, says James H. Taylor, managing partner at Hall and Hall, a national ranch and farmland broker. The reasons: rising commodity prices, a limited supply of properties and deep-pocketed owners. “There’s nothing that drives them to sell in a down market,” Taylor says.

Smaller, recreational ranches didn’t fare as well. Prices plunged roughly 40 percent during the crisis and have been slow to recover, according to Carl Palmer, cofounder of Beartooth Capital, a private equity firm that buys and restores ranches. If you’re thinking about buying now, however, that’s good news. “There’s tremendous value in owning land, particularly on streams and rivers,” says Paul Slivon, a San Francisco investment advisor who owns a roughly 200- acre ranch near Steamboat, Colo. “There are some places where you can’t get access to that water unless you own it. That’s a big deal. They can build new golf courses, but they can’t build new rivers.”

Of course, if you don’t know what you’re getting into, ranch ownership can turn into a tedious, time-consuming and costly responsibility. So follow these rules before you heed the call of the wild.

So is the notion of laying your claim and letting nature take its course. “Sometimes people buy recreational ranches and think they don’t have to do anything, but grazing and running livestock is an important part of maintaining the land,” says Palmer. These working components are also necessary for maintaining agricultural tax status and grazing rights on nearby public land. “If you come at it thinking that it’s just recreational, you’re missing the boat.”

Water rights are another key consideration. “There are all kinds of nuances with water,” says Maher. Buyers not only need to understand the extent of their water rights but also get a handle on historic flows at their portion of the stream or river. Public access, which varies from state to state and often catches landowners unaware, is also a concern. “If you’re a serious angler, you want to understand access laws and what rights the public has to fish your property,” he adds.

Mineral rights can be even more complicated. Because land rights and mineral rights often don’t go hand-in-hand, it’s important to understand what lies beneath. If another owner has a claim, there is the possibility that they’ll mine or drill on your property at some future time, and you won’t earn a penny.

Another twist is the conservation easement, which protects land from development. You can sell such an easement to an organization with an environmental interest in protecting a portion of your land or donate it for a deduction equal to the difference in the appraised value of the land before and after restrictions. Whether conservation easements detract from the value of the land depends; in some areas, restricting use of the land will have a dollar-for-dollar impact. In other places, it may actually improve the value over time, says Palmer, because future buyers may pay a premium to be near land that can’t be developed.

Get your ranch hands

The acquisition and maintenance of your property may entail hiring a team of experts, from geologists and aqua biologists to irrigation and rangeland specialists. In many cases, owners will hire ranch managers or management firms to handle all the details. A well-run ranch should generate enough income to more than cover the cost of management, says U.S. Trust’s Taylor. A typical management fee is 50 basis points of market value plus 7 percent of income.

Get a lay of the land

A ranch means many different things to many different people. For some, it’s a 25-acre retreat with sweeping views, a couple of horses and easy access to civilization. For others, a ranch is a full-time operation encompassing thousands of acres and multiple sources of income, from cattle and hay production to mineral rights and hunting leases. In states such as Colorado, Idaho and Montana, working ranches typically start around 10,000 acres at a minimum of about $1,000 an acre, says Ben Pierce, a buyer’s broker with Sweetwater Ranches based in Livingston, Mont.

Other buyers are focused on trout fishing and elk hunting out the back door. Good trout-fishing property, says Pierce, can cost anywhere from $3,000 to $12,000 an acre. But if you’re willing to share, fishing and hunting leases can provide additional ranch income. “People will pay $10,000 to $15,000 a head to hunt a bull elk on a unique ranch,” says Pierce.

Most buyers fall somewhere in the middle: They’re not interested in being full-time cowboys but want a recreational ranch with enough income to cover its costs. “You can have a working ranch that’s more passive,” says John Taylor, a managing director who oversees the farm and ranch division at U.S. Trust in Dallas. “In that case you’re leasing out the grazing and hunting rights.”

Buyers who view the transaction in part as a redeployment of cash—and in some cases an opportunity for a tax-advantaged 1031 exchange—tend to pay cash, says Bill Fandel, a broker with Sotheby’s International Realty in Telluride, Colo. Low-interest financing is, however, available via agricultural credit unions and specialized lending groups.

As with any real estate purchase, location is a huge factor, not just for property values but ease of access and amenities. “People often think they want to be in the middle of nowhere and then realize they don’t,” adds Fandel. Convenience typically comes with a price tag. Property within two hours of a prime location tends to command a higher price. It also tends to hold its value.

Wrangle the details

Ranches can be profitable, but there are far easier ways to make money. “I’m a Texas guy and love ranches,” says U.S. Trust’s Taylor. Even so, when clients express interest in buying a ranch, Taylor starts the conversation by trying to talk them out of it. “I want them to understand that in a lot of years they may not make money, and it actually may cost money,” he says.

With the exception of some parts of the country—such as in Texas, where there are five large cities and generally strong demand for ranches—the market is illiquid and inefficient. “It’s a pretty slim market to begin with and to even suggest using a comparable sale is laughable,” says Hall and Hall’s Taylor.

Where ranch owners go wrong, says Sweetwater’s Pierce, is spending on areas that don’t improve the value and may even detract from it. The biggest mistake: spending too much on the main house or superfluous outbuildings and landscaping. “We call these white elephants,” Pierce says: One man’s castle might be another’s $5 million teardown.

“We always tell the clients, own the ranch for a while and start small,” says John Taylor. “If you over-improve the ranch, the only way you get the value out is if someone likes the exact same thing that you like.”

What Does 500+ Acres of Rural Land Cost You Near Houston or Dallas-Fort Worth?

By Troy Corman, founder of t2ranches.com

Large tracts of land for sale in Texas near the major metropolitan areas are becoming more harder to come by – particularly in the Texas triangle, the area between San Antonio, Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth. We took a look at land sales of 500 acres or more recorded by the North Texas Real Estate Information System (NTREIS) and the Houston Association of Realtors (HAR) multiple listing services. Keep in mind, there are some sales and sale prices that weren’t shared publicly, but we should have enough data to give you a general idea of land values in Texas.

We limited the sales to land that didn’t have residential homes, since the size and quality of a home can vary quite a bit when it comes to farm and ranch properties in Texas.

In Houston, most of the sales of 500 acres or more occurred north of Houston, around Huntsville, with Walker county accounting for most of the closed sales. Since this area is heavily treed, additional income is often achieved due to the timber industry. As a result of the additional income potential, land for sale surrounding the Houston area year-to-date in 2019, averaged $4,293 per acre, with a median of $3,142 per acre – meaning half the tracts sold for more than $3,142 per acre, and half sold for less.

In the Dallas-Fort Worth area, most of the sales of 500 acres or more occurred west and northwest of Fort Worth. Since this land didn’t have the potential for more income through the timber industry, the price per acre decreased. Another reason may be that once you get a pretty good ways west of Fort Worth, there aren’t any major metro areas nearby. Land sales surrounding Dallas – Fort Worth averaged $2,469 per acre, with a median price of $2,411 per acre. However, twenty one sales of 500 acres or more were recorded in D-FW versus fourteen in the Houston area.

Farm and ranch land that is developed into residential or commercial real estate development sites can quickly approach the $20,000 per acre price and rise substantially from there. If you have land with a highest and best use for real estate development, you can see that we also market Texas land for commercial and residential real estate development at www.t2cre.com.

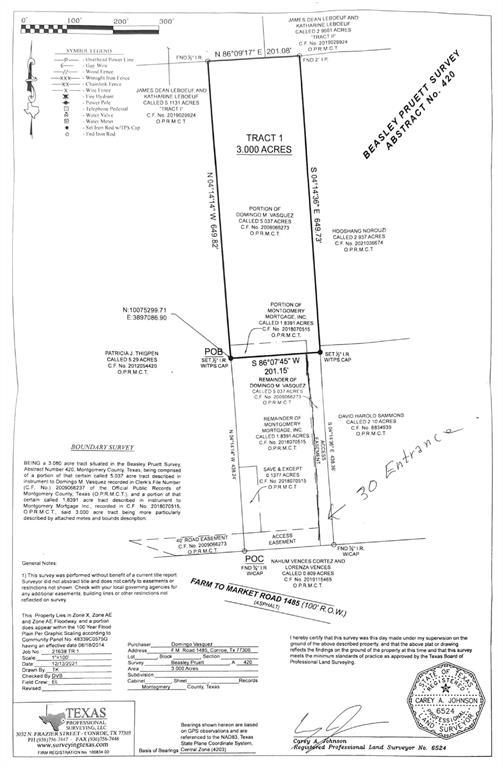

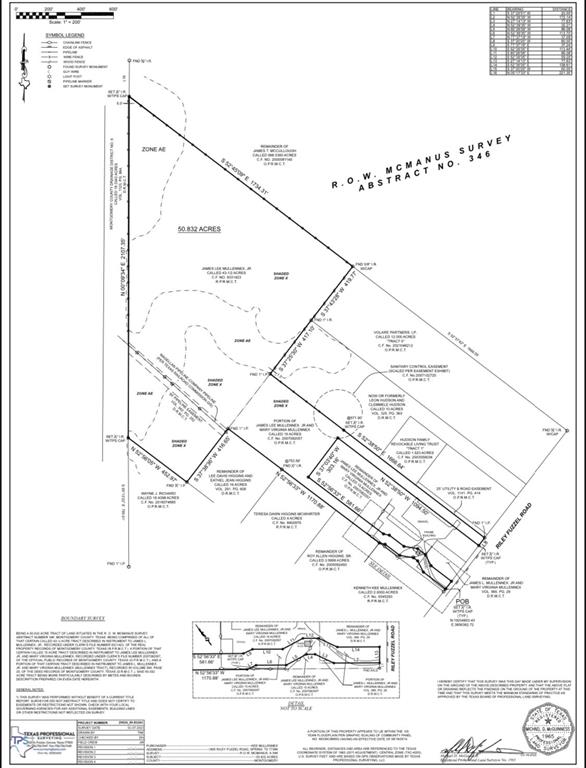

Below is Texas land for sale in Montgomery county, an area north of Houston with interesting topography and lots of trees.

Texas Triangle Beckons Ultra Wealthy Looking for Land and City Life

When Danelle and Ron Reimer moved to Austin, Texas, from Orange County, California, Last month they were intrigued by its “big little city” feel.

“We’re not really city people, but we love how welcoming Austin feels and how easy it is to get to know and to get around in,” said Danelle Reimer. “We bought in the Seven Oaks neighborhood because it’s close to downtown but also has privacy and views.”

The Reimers ’ 9,000-square-foot house, which they purchased for more than $2 million, reminds them of a Southern California-style home with its arched doorways, tile work, wood beams and stonework.

“We like a lot of space and this house has a lot of personality, too,” Ms. Reimer said.

The Reimers, who relocated for Ron’s work with a global financial services company, aren’t the only high-net-worth family to make the “Texas Triangle,” which includes Houston, Dallas and Austin, their home in recent years.

More: Tuscan-Style Estate in Texas To Hit Auction Block Next Month

The Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington metro area is ranked 10th in the world on the list of top locations for the ultra-wealthy, according to the 2019 Wealth Report from Wealth-X.

Among the ZIP codes with the highest median sales prices in the Triangle this year, according to realtor.com, are the 75225 ZIP code in Dallas, where the median sales price year-to-date through August 2019 was $1.22 million, an increase of 4.1% compared to that same period in 2018. In Houston, the median sales price in the 77005 ZIP code from January through August 2019 was $1,1 million, an 8.3% increase compared to that same period in 2018. In Austin, meanwhile, the median sales price rose 2.2% to $830,000 in the 78746 ZIP code, the highest median sales price in that city.

(Mansion Global is owned by Dow Jones. Both Dow Jones and realtor.com are owned by News Corp.)

From Penta: Christie’s to Offer Two Pairs of Chairs Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

Buyers Entering the Texas Triangle

Northern California is a big feeder market for the luxury housing market in Austin, said Gary Dolch, owner of the Austin Luxury Group with the Compass real estate brokerage in Austin.

“These buyers were often originally dipping their toes in the water and buying a second home in Austin after they’d been here for South by Southwest or another tech event,” Mr. Dolch said. “Now they’re moving here full time.”

It helps that Texas doesn’t have any state income tax, Mr. Dolch added.

“One guy told me he got the equivalent of a 36% raise just by moving from California to Texas because of taxes,” Mr. Dolch said.

More: Once Asking $8.9 Million, an East Texas Ranch Hits the Market for Half Price

Austin attracts people from Chicago, too, according to him, either members of the tech industry or retirees who want to escape winter but be able to fly back regularly to see friends and family.

And “in the last 12 months, we’ve also seen more venture capital guys and developers from New York move to Austin to build businesses here,” Mr. Dolch said.

North of Dallas, particularly in the Frisco area, top executives from major corporations like State Farm, Liberty Mutual and Toyota are moving in along with their companies, said Russell Rhodes, a real estate agent with Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices PenFed Realty in Flower Mound, Texas, near Dallas. In other neighborhoods around Dallas and Fort Worth, multimillion-dollar properties are mostly purchased by business owners, tech company leaders, oil and gas executives, professional athletes and some relocating Californians, Mr. Rhodes said.

“Dallas is a growing city,” said Rhodes. “People like it that you can get a place with land and water views and yet be close to the city and its cultural amenities.”

More: NFL Hall-of-Famer Terry Bradshaw Lists Longtime Ranch in Oklahoma

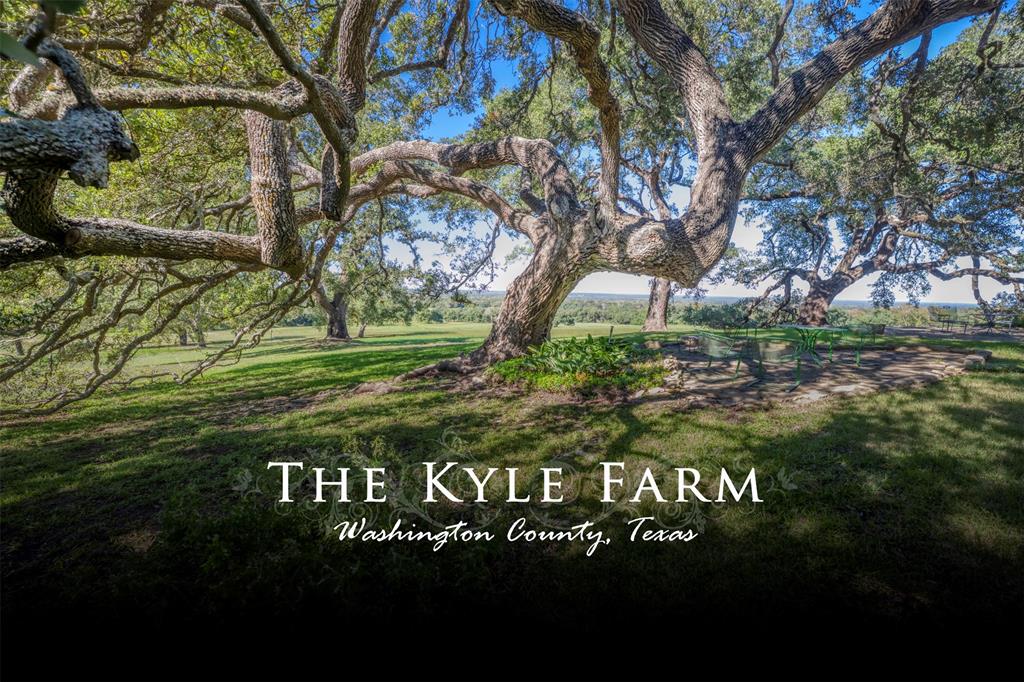

In Brenham, a community of ranches and vacation homes that’s about one hour from Houston and two hours from Austin, most of the luxury property buyers are locals who want quick access to those two cities, said Tanya Currie, a global luxury agent with Coldwell Banker Properties Unlimited in Brenham, Texas.

“Both Austin and Houston have seen good economic growth, which has brought in successful business owners,” Ms. Currie said.

She added that Texas politicians are also buying vacation homes in the area for weekend entertaining with close proximity to the cities.

“The luxury buyers in the Brenham area are what we call ‘weekend ranchers’ who want 50 to 200 acres,” said Kelli Brennan, vice president and chief operating officer of Coldwell Banker Properties Unlimited in Brenham. “The majority are cash buyers. Some are oil and gas executives, some are business owners, and a lot of them are investors from California and New Mexico who are building custom homes and then selling them in a few years.”

Buyers who keep cattle or bees or grow hay on their property may be eligible for an agricultural exemption for a tax break, Ms. Brennan said.

More: Former Dell CEO Kevin Rollins Lists Luxury Ranch in Texas

Big Entertaining Space a Must

No matter which part of the Texas Triangle they’re choosing, a common theme for most luxury home buyers is space to entertain, especially outdoors.

Thomas Markle, owner of Thomas Markle Jewelers in Houston, recently purchased the 50-acre Hidden Spring Ranch in Brenham, which he said is more manageable than some of the nearby ranches with 200 or 300 acre.

“Besides our main home in The Woodlands [in Houston] I’ve owned vacation homes in Maui and in Colorado,” Mr. Markle said. “The countryside in Brenham is unique in Texas, with rolling hills, a beautiful landscape and a small-town atmosphere, but it’s only an hour from Houston. I use our house here a few days every week. I wanted a vacation home that I could go to on the spur of the moment.”

More: The U.S.’s Permian Basin is Booming and Massive Mansions Have Followed

Markle purchased his home for $1.6 million and then spent $200,000 transforming part of the barn to a full-blown cantina with a stage for bands, a dance floor and high-tech karaoke equipment. He converted an eight-car garage to a guest house and hosts friends and family around the swimming pool and outdoor fireplace.

“Buyers in the countryside in the Texas Triangle really like the luxury farmhouse style, but they also want the ranch atmosphere with lots of acreage, oak trees, big views and ponds,” Mr. Brennan said. “We recently had a bidding war on a $4.4 million property called Stone Ridge Ranch, which has 147 acres and looks like a park with seven ponds and bridges over the water.”

A smaller estate on the market now on the street of FM 1361 in Somerville includes 19 acres with a lake, a creek and an infinity pool with a spa. Priced at $1.25 million, this weekend property has back-to-back fireplaces in the approximately 3,000-square-foot custom home, along with lighting in the lake for night fishing.

More: Texas Gangster’s Gambling Den Selling for $12 Million

The Reimers’ house in Austin has an infinity edge swimming pool with a triple-height fountain pouring water into the pool, a focal point for outdoor entertaining.

“Water is a big draw in Austin because you have this great 24-acre Lake Travis and you can build alongside it,” Mr. Dolch said. “It turns into Lady Bird Lake in the city and then you also have Lake Austin. The values of lakefront property have climbed in recent years from $6 million to $8 million a few years ago to $12 to $20 million now. If you want a new construction custom home, it can be $30 million.”

For example, a 17,800-square-foot waterfront estate on Comanche Trail with 13 acres on Lake Travis, is listed at $14.9 million. The custom home, which took four years to build and was completed in 2012, includes water and sunset views from nearly every room.

This article originally appeared on Mansion Global.

Contact Troy Corman for ranch and land properties in the Texas triangle of Houston, Austin and Dallas-Fort Worth at 832-759-1523, 214-690-9682 or troy@t2ranches.com

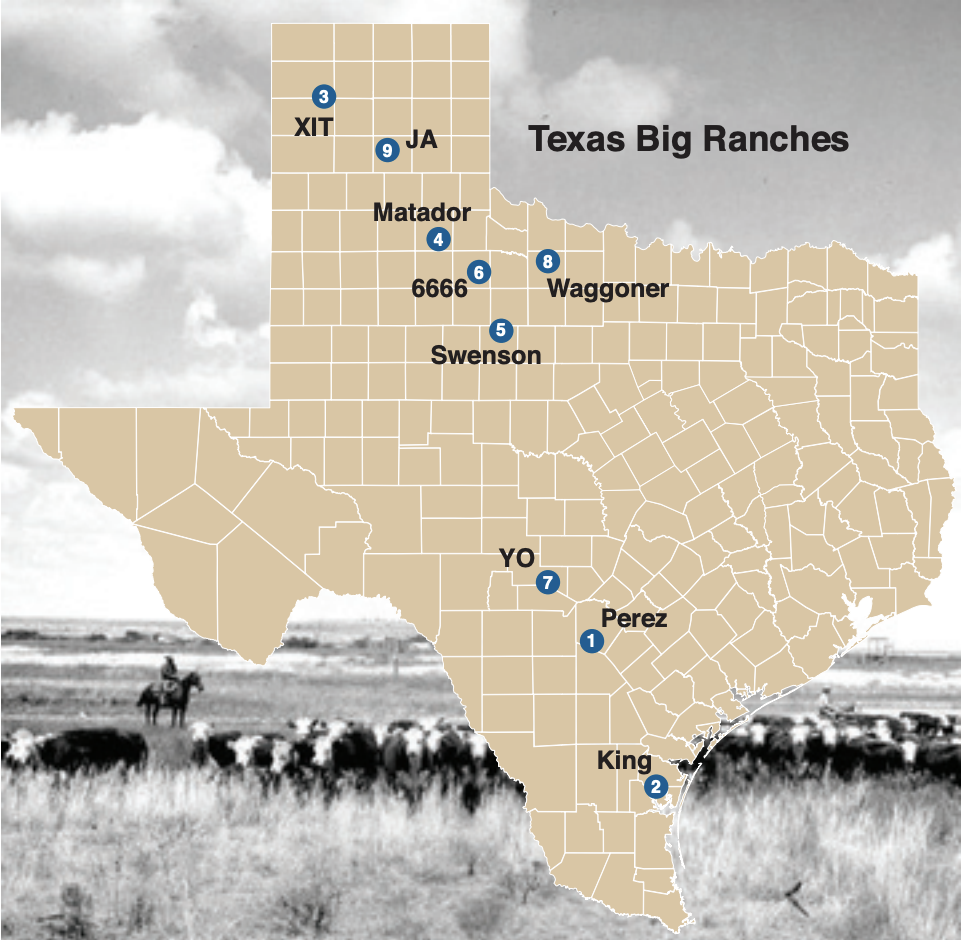

Eight of the Most Historic and Largest Ranches in Texas

Article from TexasAlmanac.com, By Mike Cox,

On July 16, 1820, Canary Island immigrant Juan Ignacio Perez sat before the proper officials in the Spanish city of San Antonio de Bexar and executed his last will and testament. The document the 59-year-old Perez signed included a declaration that he owned a substantial amount of property along the Medina River in what is now southern Bexar County.

On July 16, 1820, Canary Island immigrant Juan Ignacio Perez sat before the proper officials in the Spanish city of San Antonio de Bexar and executed his last will and testament. The document the 59-year-old Perez signed included a declaration that he owned a substantial amount of property along the Medina River in what is now southern Bexar County.

Col. Perez possessed four leagues of land on one side of the river and another league on the opposite side awarded to him by Gov. Manuel María de Salcedo for his service in the Spanish military. A Spanish unit of measurement, a league amounted to 4,428.4 acres. That meant Perez had 22,142 acres.

“On this [land],” the will further recorded, “there is a stone house and wooden corrals. . . . On these pasture lands there is some large stock both branded and unbranded, which I consider part of the property.” The veteran Indian fighter also owned “all the horses and mules marked with my brand. . . . ”

Perez acquired his first league in 1794 and the other four in 1808. One of the oldest ranches in Texas, the land Perez described that long ago summer day would stay in the same family well into the 1990s.

Ranching already had a strong foothold in Texas even before Perez began raising stock along the Medina. Capt. Blas Maria de la Garza Falcon established the Rancho Carnestolendas in 1752 on the Rio Grande where the future town of Rio Grande City would rise nearly a century later. Spanish ranchos along the Rio Grande and stock-raising operations along the San Antonio and Guadalupe rivers, which supplied beef to the missions in San Antonio and Goliad, constituted the beginning of the American cattle industry.

Also in the early 1750s, one of the San Antonio missions, San Francisco de la Espada, established a ranch about 30 miles away near present-day Floresville in Wilson County. Named Rancho de las Cabras (Ranch of the Goats), the new ranch did not represent any desire for expansion or efficiency on the part of the Spanish friars, but came as a response to complaints from San Antonio residents who grew tired of mission cattle trampling their crops. By 1756, the fortress-like ranch had 700 head of cattle, nearly 2,000 sheep, and a remuda of more than 100 horses. Three decades later, Texas still a Spanish province, a ranch connected to one of the Goliad missions had 50,000 head of cattle.

With the closing of the missions, private ranching developed as Texas attracted more settlers.

James Taylor LaBlanc—a Louisianan who Texanized his last name to White—founded the first Anglo-owned cattle ranch in Texas in 1828 near Anahuac in present-day Chambers County. From an initial stock of only a dozen cattle, White grew his herd to some 10,000 head. One visitor to White’s ranch in the 1840s described the stock as “pure Spanish breed” (longhorns).

White not only pioneered cattle-raising in Southeast Texas, he developed what would stand for many years as the industry’s prime business model—trailing cattle from the ranch where they were raised to market. Following the Texas Revolution, White and his cowhands drove cattle to buyers in New Orleans, more than 300 miles to the east.

No trace remains of White’s ranch, but Texas today has more ranches and more cattle than any other state. Texas being Texas, the state also has some of the largest ranches in the world. How much land it takes for a particular holding to be considered a ranch as opposed to simply a piece of rural property depends on its location.

In his book Historic Ranches of Texas, historian Lawrence Clayton wrote that a piece of land in East Texas with good creek or river frontage can support a cow per acre in years of normal precipitation. With that ratio, Clayton said, a landowner could justifiably call only a few hundred acres a ranch.

Along the 98th meridian, the eastern edge of the half of Texas that sees the least rainfall even in wet years, it takes 20–25 acres per cow. Farther west, the ratio increases three to four times. Accordingly, ranches in West Texas often are described by the number of sections they cover, not acres. (A section is 640 acres, or one square mile.)

The Texas Department of Agriculture says the state has 247,500 farms and ranches totaling 130.4 million acres. For 37 years, the department’s Family Land Heritage Program has been honoring families whose farms or ranches have been in continuous family ownership for more than 100 years. As of 2012, the agency has recognized 5,020 such properties.

Most of the land holdings listed by TDA are known only to their owners and families, or in their local area. But some Texas ranches—past and present—are Lone Star icons, as much a part of the state’s image as bluebonnets, oil wells, or rangy longhorns. These are some of Texas’s most historic ranches:

King Ranch

The King Ranch reigns not only as Texas’s largest spread (825,000 acres), it also has a larger-than-life history, an epic tale told over the years in numerous books, articles, and films, including a definitive volume, The King Ranch, by artist and author Tom Lea.

|

|

This 1952 photo shows Bob Kleberg trading cattle in McMullen County for the King Ranch. UNT Portal of Texas History. |

Though the state’s best-known ranch is named for founder Captain Richard King (1824–1885)—an Irish immigrant who came to Texas by way of New York and who piloted steamboats on the lower Rio Grande—it could have turned out differently.

When King met newspaperman and former Texas Ranger Gideon K. “Legs” Lewis in Corpus Christi in 1853, the two men decided to go into the cattle business together. They set up a fortified cow camp on high ground near a spring at the head of Santa Gertrudis Creek about 45 miles southwest of Corpus Christi. That summer King bought 15,500 acres for $300, and in November 1853, he sold Lewis an undivided half-interest in the land for $2,000.

Lewis bought some additional land nearby and in turn sold King half-interest. In less than a year, the two men owned more than 68,000 acres and a substantial herd of cattle and horses, called the Santa Gertrudis Ranch.

The partnership likely would have continued had not Lewis, a handsome man with an eye for pretty women, become involved with the wife of a Corpus Christi doctor. The offended doctor prescribed for Lewis a lethal dose of buckshot. With no heirs, Lewis’s estate—which included his half interest in the South Texas ranch—went on the auction block at the Nueces County Courthouse. King successfully bid on Lewis’s share of the ranch, and any possibility that the property would come to be known as the King-Lewis Ranch was as dead as the ex-ranger.

Captain King and his wife, Henrietta Chamberlain King, continued to acquire land over the years. In the spring of 1874, only a couple of decades after its founding, King Ranch gained national publicity when newspapers across the country published a column-long piece on the ranch headlined, “A Little Texas Farm.” The anonymous writer observed—quite presciently

—that, “The whole of this immense scope of country consists of the finest pasture lands in Western Texas, and must some future day be of almost incalculable value.”

When King died in 1885, Henrietta, with help from her husband’s advisors, managed the ranch for a year. In 1886, she appointed her new son-in-law, Robert Kleberg, ranch manager. By the time of Henrietta’s death in 1925, the ranch consisted of well over 1.25 million acres and supported 125,000 head of cattle and 2,500 horses. Robert Kleberg ran the ranch until his health declined. In 1918, Robert Kleberg Jr. (Mr. Bob) took the reins and continued as manager well after his father’s death in 1932.

Though King initially stocked his ranch with the wild longhorns then common all over South Texas, by crossbreeding Shorthorns and Brahmas, the ranch developed its own breed of cattle, the Santa Gertrudis. It is the first American breed of beef cattle recognized by the USDA (in 1940) and was the first new breed to be recognized worldwide in more than a century. In 1994, the ranch introduced the King Ranch Santa Cruz, a composite breed developed to meet the modern consumers’ beef expectations.

Under the leadership of Robert Kleberg Jr., who studied genetics in college and had an avid interest in livestock breeding, the King Ranch also achieved a legacy with both Thoroughbred and Quarter horses. By acquiring and breeding superior foundation stallions, the King Ranch Quarter Horse program produced Wimpy, which was awarded the number-one registration in the American Quarter Horse Association Stud Book and Registry, as well as Mr. San Peppy and Peppy San Badger, two of the all-time leading money-making sires in the National Cutting Horse Association.

In addition to its Quarter Horse lineage, the ranch produced numerous prized Thoroughbreds, including Assault, the 1946 Triple Crown winner (the only Texas horse to win the Triple Crown), and Middleground, the 1950 winner of the Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes.

Organized as a private corporation in 1934, King Ranch land in South Texas was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961 by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Its properties near Kingsville cover nearly 1,300 square miles on four divisions—Santa Gertrudis, Laureles, Norias, and Encino—and is larger than the state of Rhode Island. These divisions are located in six counties (Brooks, Jim Wells, Kenedy, Kleberg, Nueces, and Willacy) and contain terrain that varies from fertile black farmland to low-lying coastal marshes to mesquite pastures that mark the beginning of the Texas brush country.

King Ranch is still owned by the descendants of its founder and, today, is a diversified agribusiness corporation, with interests in cattle ranching, feedlot operations, farming (cotton, milo, sugar cane, and turfgrass), citrus groves, pecan processing, commodity marketing, and recreational hunting. Its retail operations include luggage, leather goods and home furnishings, farm equipment, commercial printing, and ecotourism.

JA Ranch

One summer day in 1876, Charles Goodnight and a Mexican guide, who had told Goodnight of a giant canyon that nature had gouged through the High Plains, reined their horses at the rim of Palo Duro Canyon, south of present-day Amarillo. Taking in the vastness that lay before him, the former Texas Ranger and pioneer cattleman immediately realized he had found perhaps the best location for a ranch anywhere in the Southwest. The canyon’s steep walls afforded a natural fence, and on its floor ample water flowing along the Prairie Dog Fork of the Red River would keep the mouths of his livestock wet and nourish the grass that would fill their bellies.

That visit marked the beginning of the JA Ranch, which Goodnight founded later that year with Irish-born investor John George Adair, who operated out of Denver. What began as a high-interest loan evolved into a business partnership, with Adair having two-thirds interest in the ranch and Goodnight the other third plus a salary for managing the property. Growing from an initial herd of 1,600 cattle on 2,500 acres, at its peak, the ranch grazed 100,000 head on 1.3 million acres extending across six Panhandle counties.

When Adair died in 1885, his widow, Cornelia Wadsworth Ritchie, assumed her late husband’s ownership of the sprawling ranch. Two years later, Goodnight quit the partnership and started his own ranch. The ranch is still owned by Adair heirs.

XIT Ranch

At its largest, the King Ranch never covered more than a third the size of the storied XIT—a Panhandle ranch that no longer exists. However, the XIT’s failure to survive into the modern era does not diminish its significance to Texas history.

|

|

XIT cowboys, 1891. UNT Portal of Texas History. |

Its founders were bean-counting businessmen from Chicago, not rugged individualists like Richard King, and by the time the ranch started stringing barbed wire across its vast holdings, the buffalo and the Indians had vanished from the High Plains like so many mirages. What makes the ranch unique is its connection to the red-granite State Capitol in Austin. Then cash poor but land rich, the state conveyed public land in the far northwest corner of the Panhandle to the group of investors in 1882 to finance construction of the new statehouse, an imposing structure that would architecturally rival the nation’s Capitol.

Once the biggest ranch in the world, the XIT spread over 3 million acres and stretched nearly 200 miles long and up to 30 miles wide from Hockley County on the south all the way north to the Oklahoma border. The ranch covered parts of ten High Plains counties. At its height, enclosed by 6,000 miles of barbed wire fence, the ranch ran 150,000 head of cattle, had 1,500 horses, and kept 150 cowboys on its payroll.

In the early 1900s, the XIT’s owners—struggling for a return on investment they had yet to realize—decided to discontinue raising cattle. Their strategy would be to make back their money by breaking up the huge acreage the syndicate owned and selling smaller parcels as ranches or farms. Two-thirds of the ranch had been sold by 1906, and by 1912, the last XIT cattle had been sent to market. The final piece of XIT land was conveyed to another owner in 1963.

Matador Ranch

The Matador Ranch is the third historic Texas ranch that once had more than a million acres inside its fence lines. Col. Alfred M. Britton, his nephew Cata (whose full name seems to have been lost to history), Henry Harrison Campbell, Spottswood W. Lomax, and John W. Nichols founded the ranch in 1879. By 1882, the Matador consisted of 1.5 million acres west of Wichita Falls in Cottle, Dickens, Floyd, and Motley counties. Later that year, several investors from Scotland bought the ranch, renaming it the Matador Land and Cattle Co.

Under its Scottish management, the ranch prospered and grew. At its peak period of operation, the company controlled 3 million acres, counting substantial holdings in Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Canada.

By 1951, the ranch had been sold down to roughly 800,000 acres. Lazard Freres and Co. of London bought the ranch and then subdivided it for resale. A year later, Fred C. Koch, co-founder of what later became Koch Industries, purchased a substantial amount of Matador acreage. When Koch died in 1967, his son Charles inherited the business. Today, the ranch is owned by the Matador Cattle Co., a division of the Koch Agricultural Co. In addition to continuing its long history as a cattle and horse-raising operation, the Matador offers paid hunting and guest lodging.

Four Sixes Ranch

Legend holds that Samuel Burk Burnett won the Four Sixes Ranch in a poker game holding a nearly unbeatable hand of four sixes. That makes a great story, but the 6666 brand that gave the ranch its name traces to 1868, when the then 19-year-old Burnett bought 100 head of cattle with 6666 burned on their flanks from a cattleman in Denton County.

|

|

Four Sixes cowboys. Undated, UNT Portal of Texas History. |

Originally from Missouri, Burnett drove longhorn herds up the Chisholm Trail from South Texas and ranched elsewhere on leased land before acquiring the acreage in King County in 1900 that became the Four Sixes. During its peak years, the Four Sixes had four separate divisions sprawling across nearly a third of a million acres.

In 1917, Burnett built a $100,000 ranch house at Guthrie to serve as residence for his manager and guests, as well as ranch headquarters. Stone quarried on the ranch went into the construction of the giant 11-bedroom structure, which Burnett rightly called “the finest ranch house in West Texas.”

Three years later, though Burnett already was a wealthy man, producing oil wells came in on his Dixon Creek Ranch near the town of Panhandle in Carson County. Shortly before his death in 1922, Burnett opined that oil might make a rancher more money than cattle.

The Burnett family holdings now consist of 275,000 acres, including the Dixon Creek Ranch. Today the ranch still raises cattle and thoroughbred quarter horses. The current owner is Burnett’s great-granddaughter, Anne Burnett Windfohr Marion.

Swenson Ranches

Swedish immigrant Swante M. Swenson, who came to Texas in 1838, personified the American rags-to-riches dream. When he arrived virtually pennyless in the U.S., he didn’t even speak English. When he died in 1896, he owned one of Texas’s largest and most famous ranches, the SMS.

As a merchant and hotelier in Austin in the 1850s, Swenson began acquiring vast tracts of public land well beyond the frontier line in unsettled West Texas. Forced to leave Texas in 1863 because of his opposition to secession, Swenson stayed in Mexico until after the Civil War. Moving to New York, he began a banking business.

Meanwhile, Swenson retained all his inexpensively purchased land in Texas. But that asset became a liability when the Texas Legislature began organizing new counties in West Texas and his extensive land holdings suddenly became subject to taxation.

In 1881, he tried to sell all his Texas real estate but either couldn’t find a buyer or didn’t like the offers he got. Determined to begin realizing a return on his investment, in 1882, Swenson turned management of his property over to his two sons, Eric and S. Albin Swenson. After visiting the Texas property for the first time, they divided the land into three ranches that Swenson named after his children: Ericksdahl, Mount Albin, and Elenora. Later, the Elenora was renamed the Throckmorton Ranch and Mount Albin became the Flat Top Ranch.

The Swensons, having found that they could make money off their property, continued to buy land, including in 1898 the Tongue River Ranch in King, Motley, and Dickens counties.

In 1902, the Swensons hired Frank S. Hastings as SMS manager. Over the next 20 years, Hastings produced and marketed high-grade beef and brought about numerous ranching innovations. A pioneer public relations practitioner, Hastings crafted the ranch’s slogan, “It takes a great land to produce great beef!”

The Swensons donated land for the town of Stamford on the Jones-Haskell county line, built a hotel, attracted a rail line, and even assisted in getting the town a Carnegie Library. In 1924, they constructed a brick-and-stone office building in Stamford to serve as the ranch headquarters.

Swenson family members also played a prominent role in organizing the Texas Cowboy Reunion in 1930, a rodeo and celebration held in Stamford every July 4th weekend since then. Over the years, many of the old cowboys honored at the event were waddies who had spent their entire career on one of the Swenson ranches.

In 1978, the Swenson family split the SMS Ranches into four separate companies, each owned by a group of family members. Since then, the ranches have been sold outside the family.

The YO

Through the 1920s, if a person wanted to take a deer off someone’s land, about all he needed to do was ask. But starting in the 1930s, with cattle prices suppressed by a national depression, it occurred to some ranchers that they could charge for the privilege of hunting on their land. Today, some Texas ranches make a large portion of their income by leasing land for hunting, or charging by the day or by the game animal.

One of the first ranches to diversify in this way is also one of Texas’s most historic, the famed YO Ranch in Kerr County.

Former Texas Ranger captain Charles A. Schreiner acquired more than a half million acres on the Edwards Plateau beginning in 1880. He got his start rounding up and selling longhorns, but diversified into banking and retail sales. In 1914, he divided his holdings among his eight children.

Son Walter got 69,000 acres about 40 miles west of Kerrville, the property still known as the YO. Walter managed the ranch through the terrible drought of 1917–1918 and into the Great Depression. When he died in 1933, his widow, Myrtle Schreiner, took over the operation of the ranch. A particularly forward-thinking businesswoman, she is credited with being the first Texas rancher to come up with the idea of leasing a ranch for deer and turkey hunting.

Her son Charles Schreiner III began managing the ranch in the 1950s about the time a drought even worse than the 1917 dry spell took hold. Money earned from hunters helped mitigate the impact of the drought on the ranch. Later, Schreiner started a registry for longhorn cattle and almost single-handedly saved the historic breed. He also introduced imported exotic wildlife to the ranch, pioneering another new way to make money off the land by offering hunts for trophy African game animals in the Texas Hill Country.

Schreiner’s son Louie took over operation of the ranch in the late 1980s. Following Louie’s death, Charles IV and his wife, Mary, began running the ranch, which continues to flourish as a hunting and outdoor recreation destination, as well as a working traditional ranch.

The Waggoner Ranch

While not as well known as the King Ranch, this Northwest Texas spread is three years older and at 550,000 acres, more than half its size. But unlike the King Ranch, which is made up of several non-contiguous divisions, the Waggoner Ranch is Texas’s largest cattle fiefdom behind a single fence. It stretches from near Wichita Falls eastward to Vernon, covering parts of Archer, Baylor, Foard, Knox, Wichita, and Wilbarger counties.

Dan Waggoner acquired 15,000 acres in 1850 in Wise County, registering a brand for his longhorns that consisted of three backward-facing Ds. Four years later, he dropped two of the Ds, but for years the Waggoner Ranch was best known as the Three D Ranch.

When Waggoner died in 1903, his son W.T. took over operation of the property. In 1910, he divided the ranch among his children, but in 1923 the holdings were reunited and placed into a family trust.

Cowboy humorist Will Rogers was a close friend of the Waggoner family and often visited the ranch. “I see there’s an oil well for every cow,” Rogers famously observed on one visit to the ranch in the early 1930s.

Rogers’ comment aside, Texas etiquette holds that it’s impolite to ask a rancher how many acres or sections he owns. Nor is it considered proper to inquire as to how many head a rancher runs on his place. One writer found that out when he visited the ranch in the early 1960s. When he asked a long-time Waggoner hand how many cattle grazed on the Three D, he replied, “Not as many as before the drought of the fifties.” So, how many cattle was the ranch running on the place prior to the drought, the writer asked. “More than now,” the cowboy answered.

Like its top-tier peers, the Waggoner Ranch raises cattle and quarter horses, its bottom line bolstered by oil and gas production. The company also has round 26,000 acres in cultivation.

Its cow herd is approximately 60 percent straight Hereford with 40 percent Angus-Hereford and Brangus-Hereford cross. Horses are bred for ranch work, and many still carry the bloodline of the famous quarter horse Poco Bueno.

Since its origin in the mid-1700s when Texas was a Spanish colonial province, ranching in Texas has changed dramatically. But writer-academician J. Frank Dobie, a man who grew up on a South Texas ranch before deciding that wrangling words and students beat punching cattle, remained bullish on the industry, and ranches in particular.

“As long as Western land grows grass but does not receive enough rainfall to make farming practicable,” he wrote in Up the Trail from Texas, “there will be cattle ranches and cowboys.”

– written by Mike Cox for the Texas Almanac 2014–2015. Mr. Cox is an author of many books, articles, and columns about Texas.

Water Wars Pit Rural and Urban Texas Against Each Other

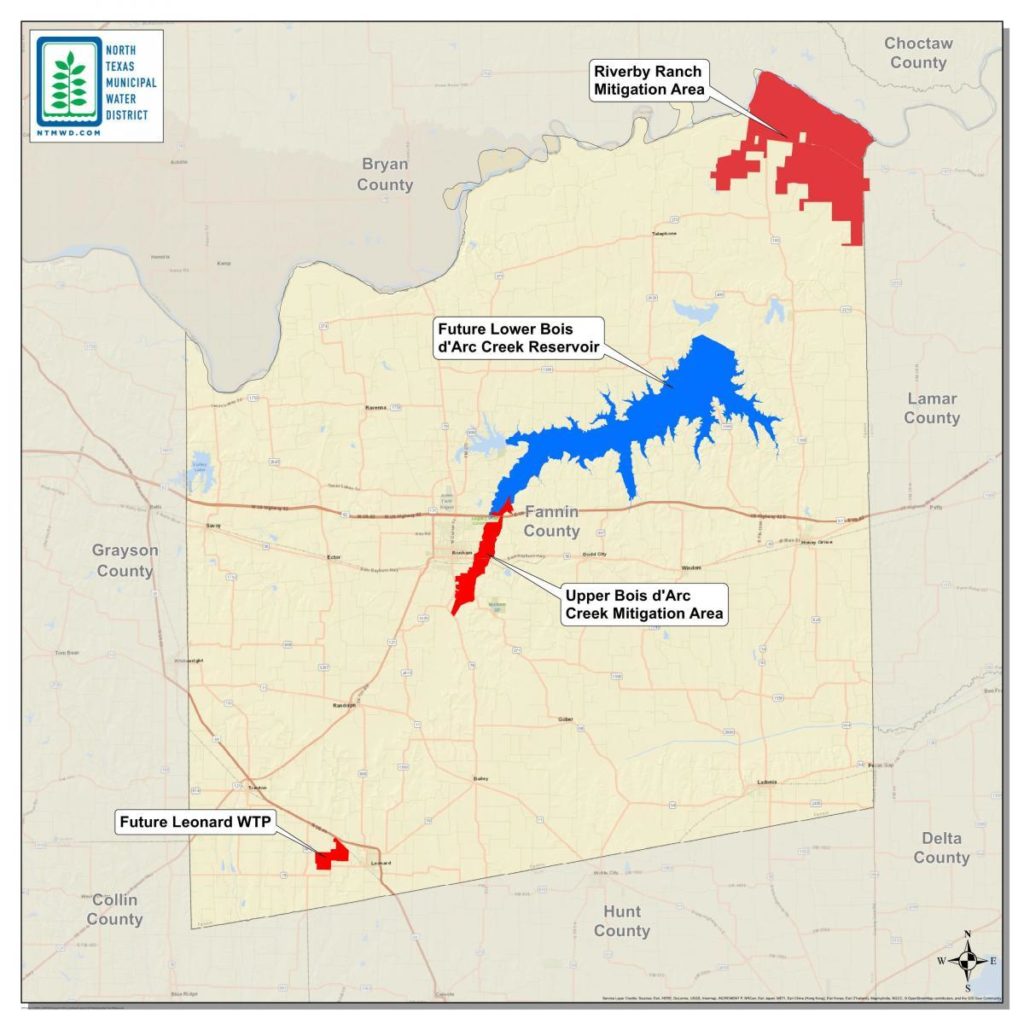

Fast-growing North Texas towns need water. But a reservoir project will displace families who have lived in Fannin County for generations.

Fast-growing North Texas towns need water. But a reservoir project will displace families who have lived in Fannin County for generations.

You know you’re getting close to Harrold Witcher’s place when you pass the water tower in Carson, a community of 22 people in northeast Texas just south of the Oklahoma border. A mere 20 minutes from the Red River, this is a part of the state that’s predicated on precipitation. Folks here can count on Bois d’Arc Creek to flood several county roads at least once a year, and a chief source of recreation is fishing in one of several nearby lakes.

All that rain makes this ideal country for growing soybeans and raising cattle on verdant green pastures. That’s the line of business Harold Witcher is in.

Witcher, who also raises cattle on an additional 300 acres in eastern Fannin County—which is about an hour northeast of the water district’s headquarters in Wylie—has worked in agriculture for most of his life, he says. He credits ample rainfall for much of his success. Bonham, the county seat, sees 46 inches of rain a year, nearly double the amount the West Texas town of Abilene gets. But the rain that’s helped keep 68-year-old Witcher in crops and cattle for so long will be his undoing. With the help of a Dallas-area water supplier, Witcher’s land, along with his business, will soon be underwater.

Fannin County is the future home of the Bois d’Arc Lake Reservoir, a 26-square mile body of water that will stretch across the central and eastern parts of the county and hold 367,609 acre-feet of water. The projected cost of building the reservoir, which includes a pump station, a dam, and pipelines, is $1.6 billion. Once completed, it’ll be the first major reservoir built in Texas in nearly three decades.

Mike Rickman, deputy director of the North Texas Municipal Water District, said the project is needed to ensure the region doesn’t run out of water in the next big drought.

“We need enough supply to take us through what is the equivalent of the drought of record,” Rickman said. “In our world, that would be seven years in duration. It is a lot of water that’s needed.”

The water district, which is building the Bois d’Arc lake, plans to pipe water from the reservoir 40 miles southwest to McKinney starting in 2022. The town of McKinney, along with other suburban enclaves bordering Dallas, represent some of the fastest growing communities in the entire nation. Rickman says all those residents expect a steady source of water—but meeting the demand is a tall order.

But some residents of Fannin County, including Witcher, will pay a high price to provide urbanites with water—namely their homes and land that’s been in the family for generations.

“A lot of the people in urban areas I’ve talked to about this that were raised in the urban environment, they say, well, just go get yourself another place,” Witcher said. “That is easier said than done. You just can’t go replace something that you’ve worked at your whole life. It’s not like going and buying a new house. It’s not the same.”

The Bois d’Arc project is one answer to a perennial question asked by water providers in Texas metros: Where will we find our future water source? Historically, they’ve eyed rural areas to fill that need, said Jim Blackburn, a Texas water expert and professor of environmental law at Rice University.

“It has been a priority for many, many decades in Texas for municipalities to be supplied with all the water they need in various and sundry ways, mainly though reservoirs and sometimes through groundwater development,” Blackburn said. “Historically, reservoirs have been located in rural areas and there’s no question that there’s been disproportionate impact.”

The Bois d’Arc project isn’t the only one where urban interests appear to be foisted on rural areas. The North Texas Municipal Water District is pursuing another major reservoir project in East Texas, called the Marvin Nichols Reservoir, where people’s homes and productive farmland will be flooded to make a lake. In Wichita Falls, city leaders are spearheading a hotly contested project to build a new reservoir in rural Clay County, despite an outcry from ranchers who stand to lose their property.

In Fannin County, public opinion seems divided on Bois d’Arc lake. County Commissioner Jerry Magnus, whose district includes the future reservoir, said he once was against the project. He’s since come around because of the anticipated economic benefit of having thousands of workers in the area and the possibility of tourism at the lake.

“It’s a boon to Fannin County as far as economic value because it’s gonna bring people who’ve got some money, and it takes money to make money,” Magnus said.

But Paul Vaughn, a farmer who was eating lunch at the senior citizen’s center in Bonham when I visited in June, said the Bois d’Arc project was simply a ploy to shift the cost of developing urban Texas to rural residents.

“In my personal opinion, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer all the time,” Vaughn said. “Fannin County isn’t gonna gain much off this lake for years to come. You can forget that.”

Either way, there’s nothing Witcher or other affected landowners can do to stop the project. The water district has the power of eminent domain, and he and other area landowners who stood to have their land flooded for the reservoir have unsuccessfully gone to court over the matter. Some of them have reached settlement agreements with the district, though they say they’re unable to speak on the confidential agreements.

Witcher says he and his wife plan to move from their home to property her family owns near Windom, about 20 miles away, this year. He says he’ll try to start his farming and ranching operation all over again from there—if he lives long enough to do it.

“Thing about it is I’m 68 years old,” Witcher said. “I don’t have a lot of productive time left to get a place back in production.”

More of these fights are expected to crop up as time goes on. By 2070, the state projects water demand to rise from 18.4 million acre-feet per year to 21.6 million. It also includes plans to build 26 new reservoirs, a strategy that some critics say is expensive, inefficient, and tends to disenfranchise rural people. Janice Bezanson, executive director of the Texas Conservation Alliance, a group that generally opposes new reservoir projects, notes that a significant portion of water used by households in suburban North Texas is used simply for landscape irrigation.

“We’re planning to spend billions of dollars, force people to sell land that provides their livelihoods . . . so we can build reservoirs so that people can water their lawns,” Bezanson said.

Rickman, the water district official, notes that Bois d’Arc Creek is only expected to meet the region’s future water needs through the year 2040. They’re already searching for new ways to bring water into the area, which may further impact surrounding rural counties.

“Even though we already have this reservoir online,” Rickman said, “we’re already looking for our next source of water because we know we’re going to continue to grow.”

This story was produced and published with KUT/Texas Standard.

If you’re interested in buying or selling land in Fannin County or north Texas, contact Troy Corman, with t2ranches.com at 214-690-9682 or email troy@t2ranches.com.