The Frio River snaked south through the hills of Uvalde County, its clear waters coursing over a bed of white, fractured limestone in the recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer.

The Frio River snaked south through the hills of Uvalde County, its clear waters coursing over a bed of white, fractured limestone in the recharge zone of the Edwards Aquifer.

The river had flowed into — and underneath — Dripstone Ranch, nearly 2,000 acres of undeveloped ranchland named after a system of nine caves that open into the hillsides and stretch hundreds of feet beneath the earth. One of them, Queen Frio Cave, contains an underground stream that flows swiftly east for San Antonio residents to drink.

To those in the business of acquiring land to protect San Antonio’s water supply, Dripstone had developed a reputation over the years as an alluring and elusive prospect, earning it a nickname.

The White Whale.

“Dripstone. That’s a big one,” said Francine Romero, who chairs an advisory board that oversees the city’s Edwards Aquifer Protection Program. “They used to call it the White Whale, the guys from the Nature Conservancy, because it was just so attractive to the program.”

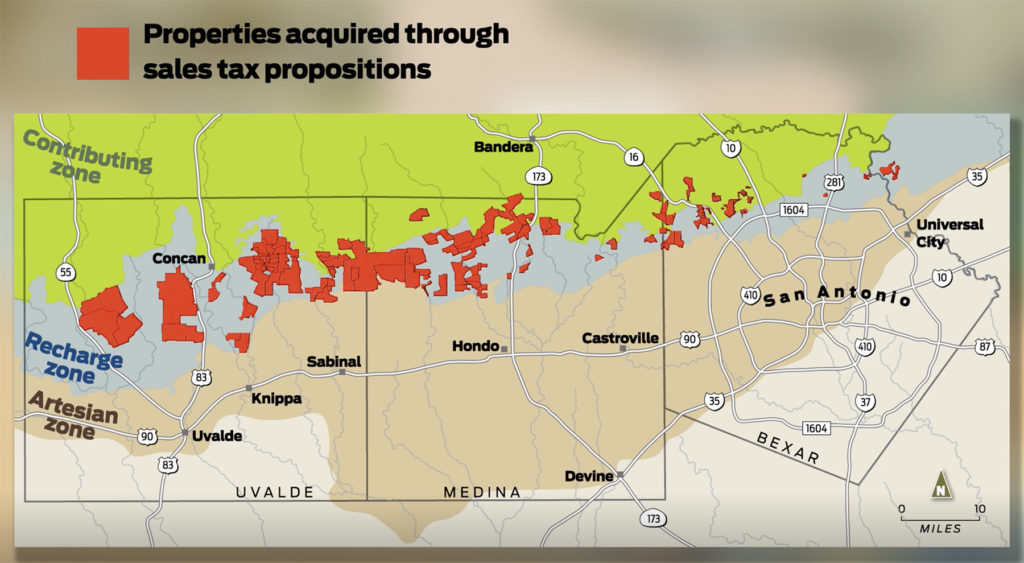

Voters authorized the EAPP two decades ago to prevent contamination of the water that recharges the aquifer — a source of drinking water for more than 2 million people — and to maintain enough permeable surface to allow it to refill. Save for a relative handful of outright land acquisitions, the program has accomplished this mostly through the purchase of conservation easements, a less costly transaction under which a landowner keeps the deed to the property but agrees to limit development. Read full article

See the video of the Edwards Aquifer Recharge zone area in Texas