Article from TexasAlmanac.com, By Mike Cox,

On July 16, 1820, Canary Island immigrant Juan Ignacio Perez sat before the proper officials in the Spanish city of San Antonio de Bexar and executed his last will and testament. The document the 59-year-old Perez signed included a declaration that he owned a substantial amount of property along the Medina River in what is now southern Bexar County.

On July 16, 1820, Canary Island immigrant Juan Ignacio Perez sat before the proper officials in the Spanish city of San Antonio de Bexar and executed his last will and testament. The document the 59-year-old Perez signed included a declaration that he owned a substantial amount of property along the Medina River in what is now southern Bexar County.

Col. Perez possessed four leagues of land on one side of the river and another league on the opposite side awarded to him by Gov. Manuel María de Salcedo for his service in the Spanish military. A Spanish unit of measurement, a league amounted to 4,428.4 acres. That meant Perez had 22,142 acres.

“On this [land],” the will further recorded, “there is a stone house and wooden corrals. . . . On these pasture lands there is some large stock both branded and unbranded, which I consider part of the property.” The veteran Indian fighter also owned “all the horses and mules marked with my brand. . . . ”

Perez acquired his first league in 1794 and the other four in 1808. One of the oldest ranches in Texas, the land Perez described that long ago summer day would stay in the same family well into the 1990s.

Ranching already had a strong foothold in Texas even before Perez began raising stock along the Medina. Capt. Blas Maria de la Garza Falcon established the Rancho Carnestolendas in 1752 on the Rio Grande where the future town of Rio Grande City would rise nearly a century later. Spanish ranchos along the Rio Grande and stock-raising operations along the San Antonio and Guadalupe rivers, which supplied beef to the missions in San Antonio and Goliad, constituted the beginning of the American cattle industry.

Also in the early 1750s, one of the San Antonio missions, San Francisco de la Espada, established a ranch about 30 miles away near present-day Floresville in Wilson County. Named Rancho de las Cabras (Ranch of the Goats), the new ranch did not represent any desire for expansion or efficiency on the part of the Spanish friars, but came as a response to complaints from San Antonio residents who grew tired of mission cattle trampling their crops. By 1756, the fortress-like ranch had 700 head of cattle, nearly 2,000 sheep, and a remuda of more than 100 horses. Three decades later, Texas still a Spanish province, a ranch connected to one of the Goliad missions had 50,000 head of cattle.

With the closing of the missions, private ranching developed as Texas attracted more settlers.

James Taylor LaBlanc—a Louisianan who Texanized his last name to White—founded the first Anglo-owned cattle ranch in Texas in 1828 near Anahuac in present-day Chambers County. From an initial stock of only a dozen cattle, White grew his herd to some 10,000 head. One visitor to White’s ranch in the 1840s described the stock as “pure Spanish breed” (longhorns).

White not only pioneered cattle-raising in Southeast Texas, he developed what would stand for many years as the industry’s prime business model—trailing cattle from the ranch where they were raised to market. Following the Texas Revolution, White and his cowhands drove cattle to buyers in New Orleans, more than 300 miles to the east.

No trace remains of White’s ranch, but Texas today has more ranches and more cattle than any other state. Texas being Texas, the state also has some of the largest ranches in the world. How much land it takes for a particular holding to be considered a ranch as opposed to simply a piece of rural property depends on its location.

In his book Historic Ranches of Texas, historian Lawrence Clayton wrote that a piece of land in East Texas with good creek or river frontage can support a cow per acre in years of normal precipitation. With that ratio, Clayton said, a landowner could justifiably call only a few hundred acres a ranch.

Along the 98th meridian, the eastern edge of the half of Texas that sees the least rainfall even in wet years, it takes 20–25 acres per cow. Farther west, the ratio increases three to four times. Accordingly, ranches in West Texas often are described by the number of sections they cover, not acres. (A section is 640 acres, or one square mile.)

The Texas Department of Agriculture says the state has 247,500 farms and ranches totaling 130.4 million acres. For 37 years, the department’s Family Land Heritage Program has been honoring families whose farms or ranches have been in continuous family ownership for more than 100 years. As of 2012, the agency has recognized 5,020 such properties.

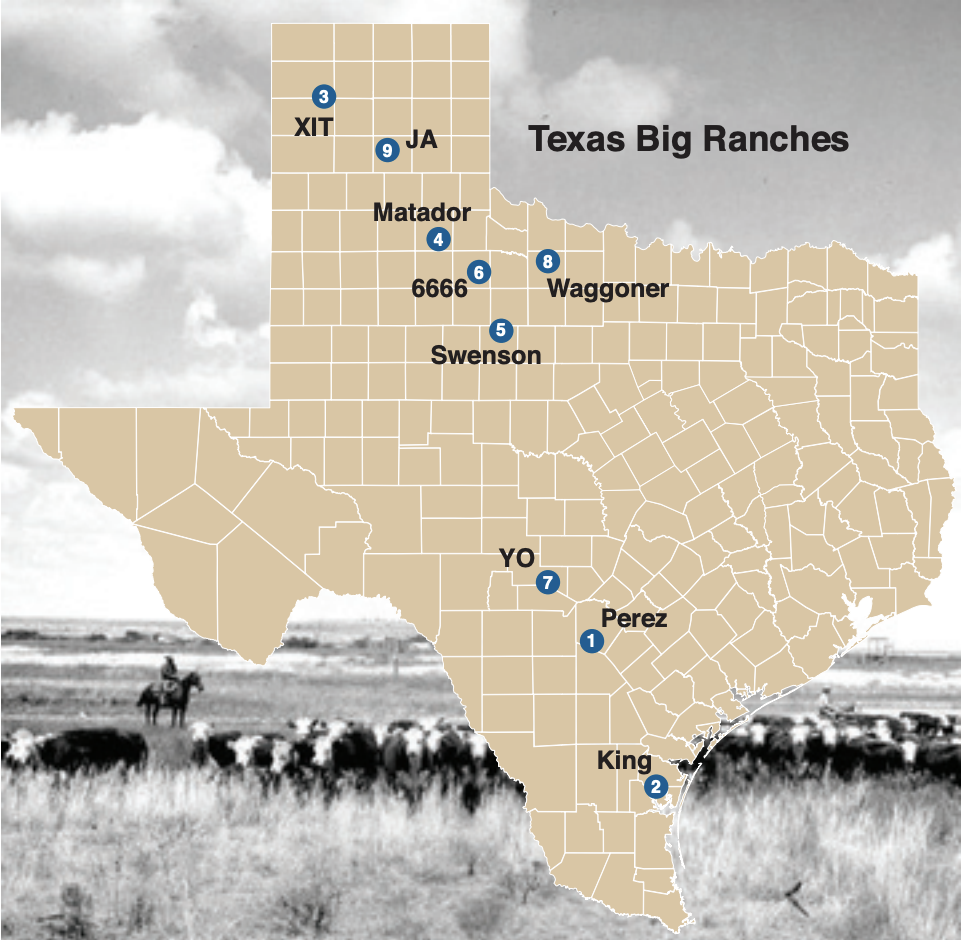

Most of the land holdings listed by TDA are known only to their owners and families, or in their local area. But some Texas ranches—past and present—are Lone Star icons, as much a part of the state’s image as bluebonnets, oil wells, or rangy longhorns. These are some of Texas’s most historic ranches:

King Ranch

The King Ranch reigns not only as Texas’s largest spread (825,000 acres), it also has a larger-than-life history, an epic tale told over the years in numerous books, articles, and films, including a definitive volume, The King Ranch, by artist and author Tom Lea.

|

|

This 1952 photo shows Bob Kleberg trading cattle in McMullen County for the King Ranch. UNT Portal of Texas History. |

Though the state’s best-known ranch is named for founder Captain Richard King (1824–1885)—an Irish immigrant who came to Texas by way of New York and who piloted steamboats on the lower Rio Grande—it could have turned out differently.

When King met newspaperman and former Texas Ranger Gideon K. “Legs” Lewis in Corpus Christi in 1853, the two men decided to go into the cattle business together. They set up a fortified cow camp on high ground near a spring at the head of Santa Gertrudis Creek about 45 miles southwest of Corpus Christi. That summer King bought 15,500 acres for $300, and in November 1853, he sold Lewis an undivided half-interest in the land for $2,000.

Lewis bought some additional land nearby and in turn sold King half-interest. In less than a year, the two men owned more than 68,000 acres and a substantial herd of cattle and horses, called the Santa Gertrudis Ranch.

The partnership likely would have continued had not Lewis, a handsome man with an eye for pretty women, become involved with the wife of a Corpus Christi doctor. The offended doctor prescribed for Lewis a lethal dose of buckshot. With no heirs, Lewis’s estate—which included his half interest in the South Texas ranch—went on the auction block at the Nueces County Courthouse. King successfully bid on Lewis’s share of the ranch, and any possibility that the property would come to be known as the King-Lewis Ranch was as dead as the ex-ranger.

Captain King and his wife, Henrietta Chamberlain King, continued to acquire land over the years. In the spring of 1874, only a couple of decades after its founding, King Ranch gained national publicity when newspapers across the country published a column-long piece on the ranch headlined, “A Little Texas Farm.” The anonymous writer observed—quite presciently

—that, “The whole of this immense scope of country consists of the finest pasture lands in Western Texas, and must some future day be of almost incalculable value.”

When King died in 1885, Henrietta, with help from her husband’s advisors, managed the ranch for a year. In 1886, she appointed her new son-in-law, Robert Kleberg, ranch manager. By the time of Henrietta’s death in 1925, the ranch consisted of well over 1.25 million acres and supported 125,000 head of cattle and 2,500 horses. Robert Kleberg ran the ranch until his health declined. In 1918, Robert Kleberg Jr. (Mr. Bob) took the reins and continued as manager well after his father’s death in 1932.

Though King initially stocked his ranch with the wild longhorns then common all over South Texas, by crossbreeding Shorthorns and Brahmas, the ranch developed its own breed of cattle, the Santa Gertrudis. It is the first American breed of beef cattle recognized by the USDA (in 1940) and was the first new breed to be recognized worldwide in more than a century. In 1994, the ranch introduced the King Ranch Santa Cruz, a composite breed developed to meet the modern consumers’ beef expectations.

Under the leadership of Robert Kleberg Jr., who studied genetics in college and had an avid interest in livestock breeding, the King Ranch also achieved a legacy with both Thoroughbred and Quarter horses. By acquiring and breeding superior foundation stallions, the King Ranch Quarter Horse program produced Wimpy, which was awarded the number-one registration in the American Quarter Horse Association Stud Book and Registry, as well as Mr. San Peppy and Peppy San Badger, two of the all-time leading money-making sires in the National Cutting Horse Association.

In addition to its Quarter Horse lineage, the ranch produced numerous prized Thoroughbreds, including Assault, the 1946 Triple Crown winner (the only Texas horse to win the Triple Crown), and Middleground, the 1950 winner of the Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes.

Organized as a private corporation in 1934, King Ranch land in South Texas was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1961 by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Its properties near Kingsville cover nearly 1,300 square miles on four divisions—Santa Gertrudis, Laureles, Norias, and Encino—and is larger than the state of Rhode Island. These divisions are located in six counties (Brooks, Jim Wells, Kenedy, Kleberg, Nueces, and Willacy) and contain terrain that varies from fertile black farmland to low-lying coastal marshes to mesquite pastures that mark the beginning of the Texas brush country.

King Ranch is still owned by the descendants of its founder and, today, is a diversified agribusiness corporation, with interests in cattle ranching, feedlot operations, farming (cotton, milo, sugar cane, and turfgrass), citrus groves, pecan processing, commodity marketing, and recreational hunting. Its retail operations include luggage, leather goods and home furnishings, farm equipment, commercial printing, and ecotourism.

JA Ranch

One summer day in 1876, Charles Goodnight and a Mexican guide, who had told Goodnight of a giant canyon that nature had gouged through the High Plains, reined their horses at the rim of Palo Duro Canyon, south of present-day Amarillo. Taking in the vastness that lay before him, the former Texas Ranger and pioneer cattleman immediately realized he had found perhaps the best location for a ranch anywhere in the Southwest. The canyon’s steep walls afforded a natural fence, and on its floor ample water flowing along the Prairie Dog Fork of the Red River would keep the mouths of his livestock wet and nourish the grass that would fill their bellies.

That visit marked the beginning of the JA Ranch, which Goodnight founded later that year with Irish-born investor John George Adair, who operated out of Denver. What began as a high-interest loan evolved into a business partnership, with Adair having two-thirds interest in the ranch and Goodnight the other third plus a salary for managing the property. Growing from an initial herd of 1,600 cattle on 2,500 acres, at its peak, the ranch grazed 100,000 head on 1.3 million acres extending across six Panhandle counties.

When Adair died in 1885, his widow, Cornelia Wadsworth Ritchie, assumed her late husband’s ownership of the sprawling ranch. Two years later, Goodnight quit the partnership and started his own ranch. The ranch is still owned by Adair heirs.

XIT Ranch

At its largest, the King Ranch never covered more than a third the size of the storied XIT—a Panhandle ranch that no longer exists. However, the XIT’s failure to survive into the modern era does not diminish its significance to Texas history.

|

|

XIT cowboys, 1891. UNT Portal of Texas History. |

Its founders were bean-counting businessmen from Chicago, not rugged individualists like Richard King, and by the time the ranch started stringing barbed wire across its vast holdings, the buffalo and the Indians had vanished from the High Plains like so many mirages. What makes the ranch unique is its connection to the red-granite State Capitol in Austin. Then cash poor but land rich, the state conveyed public land in the far northwest corner of the Panhandle to the group of investors in 1882 to finance construction of the new statehouse, an imposing structure that would architecturally rival the nation’s Capitol.

Once the biggest ranch in the world, the XIT spread over 3 million acres and stretched nearly 200 miles long and up to 30 miles wide from Hockley County on the south all the way north to the Oklahoma border. The ranch covered parts of ten High Plains counties. At its height, enclosed by 6,000 miles of barbed wire fence, the ranch ran 150,000 head of cattle, had 1,500 horses, and kept 150 cowboys on its payroll.

In the early 1900s, the XIT’s owners—struggling for a return on investment they had yet to realize—decided to discontinue raising cattle. Their strategy would be to make back their money by breaking up the huge acreage the syndicate owned and selling smaller parcels as ranches or farms. Two-thirds of the ranch had been sold by 1906, and by 1912, the last XIT cattle had been sent to market. The final piece of XIT land was conveyed to another owner in 1963.

Matador Ranch

The Matador Ranch is the third historic Texas ranch that once had more than a million acres inside its fence lines. Col. Alfred M. Britton, his nephew Cata (whose full name seems to have been lost to history), Henry Harrison Campbell, Spottswood W. Lomax, and John W. Nichols founded the ranch in 1879. By 1882, the Matador consisted of 1.5 million acres west of Wichita Falls in Cottle, Dickens, Floyd, and Motley counties. Later that year, several investors from Scotland bought the ranch, renaming it the Matador Land and Cattle Co.

Under its Scottish management, the ranch prospered and grew. At its peak period of operation, the company controlled 3 million acres, counting substantial holdings in Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Canada.

By 1951, the ranch had been sold down to roughly 800,000 acres. Lazard Freres and Co. of London bought the ranch and then subdivided it for resale. A year later, Fred C. Koch, co-founder of what later became Koch Industries, purchased a substantial amount of Matador acreage. When Koch died in 1967, his son Charles inherited the business. Today, the ranch is owned by the Matador Cattle Co., a division of the Koch Agricultural Co. In addition to continuing its long history as a cattle and horse-raising operation, the Matador offers paid hunting and guest lodging.

Four Sixes Ranch

Legend holds that Samuel Burk Burnett won the Four Sixes Ranch in a poker game holding a nearly unbeatable hand of four sixes. That makes a great story, but the 6666 brand that gave the ranch its name traces to 1868, when the then 19-year-old Burnett bought 100 head of cattle with 6666 burned on their flanks from a cattleman in Denton County.

|

|

Four Sixes cowboys. Undated, UNT Portal of Texas History. |

Originally from Missouri, Burnett drove longhorn herds up the Chisholm Trail from South Texas and ranched elsewhere on leased land before acquiring the acreage in King County in 1900 that became the Four Sixes. During its peak years, the Four Sixes had four separate divisions sprawling across nearly a third of a million acres.

In 1917, Burnett built a $100,000 ranch house at Guthrie to serve as residence for his manager and guests, as well as ranch headquarters. Stone quarried on the ranch went into the construction of the giant 11-bedroom structure, which Burnett rightly called “the finest ranch house in West Texas.”

Three years later, though Burnett already was a wealthy man, producing oil wells came in on his Dixon Creek Ranch near the town of Panhandle in Carson County. Shortly before his death in 1922, Burnett opined that oil might make a rancher more money than cattle.

The Burnett family holdings now consist of 275,000 acres, including the Dixon Creek Ranch. Today the ranch still raises cattle and thoroughbred quarter horses. The current owner is Burnett’s great-granddaughter, Anne Burnett Windfohr Marion.

Swenson Ranches

Swedish immigrant Swante M. Swenson, who came to Texas in 1838, personified the American rags-to-riches dream. When he arrived virtually pennyless in the U.S., he didn’t even speak English. When he died in 1896, he owned one of Texas’s largest and most famous ranches, the SMS.

As a merchant and hotelier in Austin in the 1850s, Swenson began acquiring vast tracts of public land well beyond the frontier line in unsettled West Texas. Forced to leave Texas in 1863 because of his opposition to secession, Swenson stayed in Mexico until after the Civil War. Moving to New York, he began a banking business.

Meanwhile, Swenson retained all his inexpensively purchased land in Texas. But that asset became a liability when the Texas Legislature began organizing new counties in West Texas and his extensive land holdings suddenly became subject to taxation.

In 1881, he tried to sell all his Texas real estate but either couldn’t find a buyer or didn’t like the offers he got. Determined to begin realizing a return on his investment, in 1882, Swenson turned management of his property over to his two sons, Eric and S. Albin Swenson. After visiting the Texas property for the first time, they divided the land into three ranches that Swenson named after his children: Ericksdahl, Mount Albin, and Elenora. Later, the Elenora was renamed the Throckmorton Ranch and Mount Albin became the Flat Top Ranch.

The Swensons, having found that they could make money off their property, continued to buy land, including in 1898 the Tongue River Ranch in King, Motley, and Dickens counties.

In 1902, the Swensons hired Frank S. Hastings as SMS manager. Over the next 20 years, Hastings produced and marketed high-grade beef and brought about numerous ranching innovations. A pioneer public relations practitioner, Hastings crafted the ranch’s slogan, “It takes a great land to produce great beef!”

The Swensons donated land for the town of Stamford on the Jones-Haskell county line, built a hotel, attracted a rail line, and even assisted in getting the town a Carnegie Library. In 1924, they constructed a brick-and-stone office building in Stamford to serve as the ranch headquarters.

Swenson family members also played a prominent role in organizing the Texas Cowboy Reunion in 1930, a rodeo and celebration held in Stamford every July 4th weekend since then. Over the years, many of the old cowboys honored at the event were waddies who had spent their entire career on one of the Swenson ranches.

In 1978, the Swenson family split the SMS Ranches into four separate companies, each owned by a group of family members. Since then, the ranches have been sold outside the family.

The YO

Through the 1920s, if a person wanted to take a deer off someone’s land, about all he needed to do was ask. But starting in the 1930s, with cattle prices suppressed by a national depression, it occurred to some ranchers that they could charge for the privilege of hunting on their land. Today, some Texas ranches make a large portion of their income by leasing land for hunting, or charging by the day or by the game animal.

One of the first ranches to diversify in this way is also one of Texas’s most historic, the famed YO Ranch in Kerr County.

Former Texas Ranger captain Charles A. Schreiner acquired more than a half million acres on the Edwards Plateau beginning in 1880. He got his start rounding up and selling longhorns, but diversified into banking and retail sales. In 1914, he divided his holdings among his eight children.

Son Walter got 69,000 acres about 40 miles west of Kerrville, the property still known as the YO. Walter managed the ranch through the terrible drought of 1917–1918 and into the Great Depression. When he died in 1933, his widow, Myrtle Schreiner, took over the operation of the ranch. A particularly forward-thinking businesswoman, she is credited with being the first Texas rancher to come up with the idea of leasing a ranch for deer and turkey hunting.

Her son Charles Schreiner III began managing the ranch in the 1950s about the time a drought even worse than the 1917 dry spell took hold. Money earned from hunters helped mitigate the impact of the drought on the ranch. Later, Schreiner started a registry for longhorn cattle and almost single-handedly saved the historic breed. He also introduced imported exotic wildlife to the ranch, pioneering another new way to make money off the land by offering hunts for trophy African game animals in the Texas Hill Country.

Schreiner’s son Louie took over operation of the ranch in the late 1980s. Following Louie’s death, Charles IV and his wife, Mary, began running the ranch, which continues to flourish as a hunting and outdoor recreation destination, as well as a working traditional ranch.

The Waggoner Ranch

While not as well known as the King Ranch, this Northwest Texas spread is three years older and at 550,000 acres, more than half its size. But unlike the King Ranch, which is made up of several non-contiguous divisions, the Waggoner Ranch is Texas’s largest cattle fiefdom behind a single fence. It stretches from near Wichita Falls eastward to Vernon, covering parts of Archer, Baylor, Foard, Knox, Wichita, and Wilbarger counties.

Dan Waggoner acquired 15,000 acres in 1850 in Wise County, registering a brand for his longhorns that consisted of three backward-facing Ds. Four years later, he dropped two of the Ds, but for years the Waggoner Ranch was best known as the Three D Ranch.

When Waggoner died in 1903, his son W.T. took over operation of the property. In 1910, he divided the ranch among his children, but in 1923 the holdings were reunited and placed into a family trust.

Cowboy humorist Will Rogers was a close friend of the Waggoner family and often visited the ranch. “I see there’s an oil well for every cow,” Rogers famously observed on one visit to the ranch in the early 1930s.

Rogers’ comment aside, Texas etiquette holds that it’s impolite to ask a rancher how many acres or sections he owns. Nor is it considered proper to inquire as to how many head a rancher runs on his place. One writer found that out when he visited the ranch in the early 1960s. When he asked a long-time Waggoner hand how many cattle grazed on the Three D, he replied, “Not as many as before the drought of the fifties.” So, how many cattle was the ranch running on the place prior to the drought, the writer asked. “More than now,” the cowboy answered.

Like its top-tier peers, the Waggoner Ranch raises cattle and quarter horses, its bottom line bolstered by oil and gas production. The company also has round 26,000 acres in cultivation.

Its cow herd is approximately 60 percent straight Hereford with 40 percent Angus-Hereford and Brangus-Hereford cross. Horses are bred for ranch work, and many still carry the bloodline of the famous quarter horse Poco Bueno.

Since its origin in the mid-1700s when Texas was a Spanish colonial province, ranching in Texas has changed dramatically. But writer-academician J. Frank Dobie, a man who grew up on a South Texas ranch before deciding that wrangling words and students beat punching cattle, remained bullish on the industry, and ranches in particular.

“As long as Western land grows grass but does not receive enough rainfall to make farming practicable,” he wrote in Up the Trail from Texas, “there will be cattle ranches and cowboys.”

– written by Mike Cox for the Texas Almanac 2014–2015. Mr. Cox is an author of many books, articles, and columns about Texas.